How to Handle Legacy Decluttering: A Compassionate Guide to Letting Go

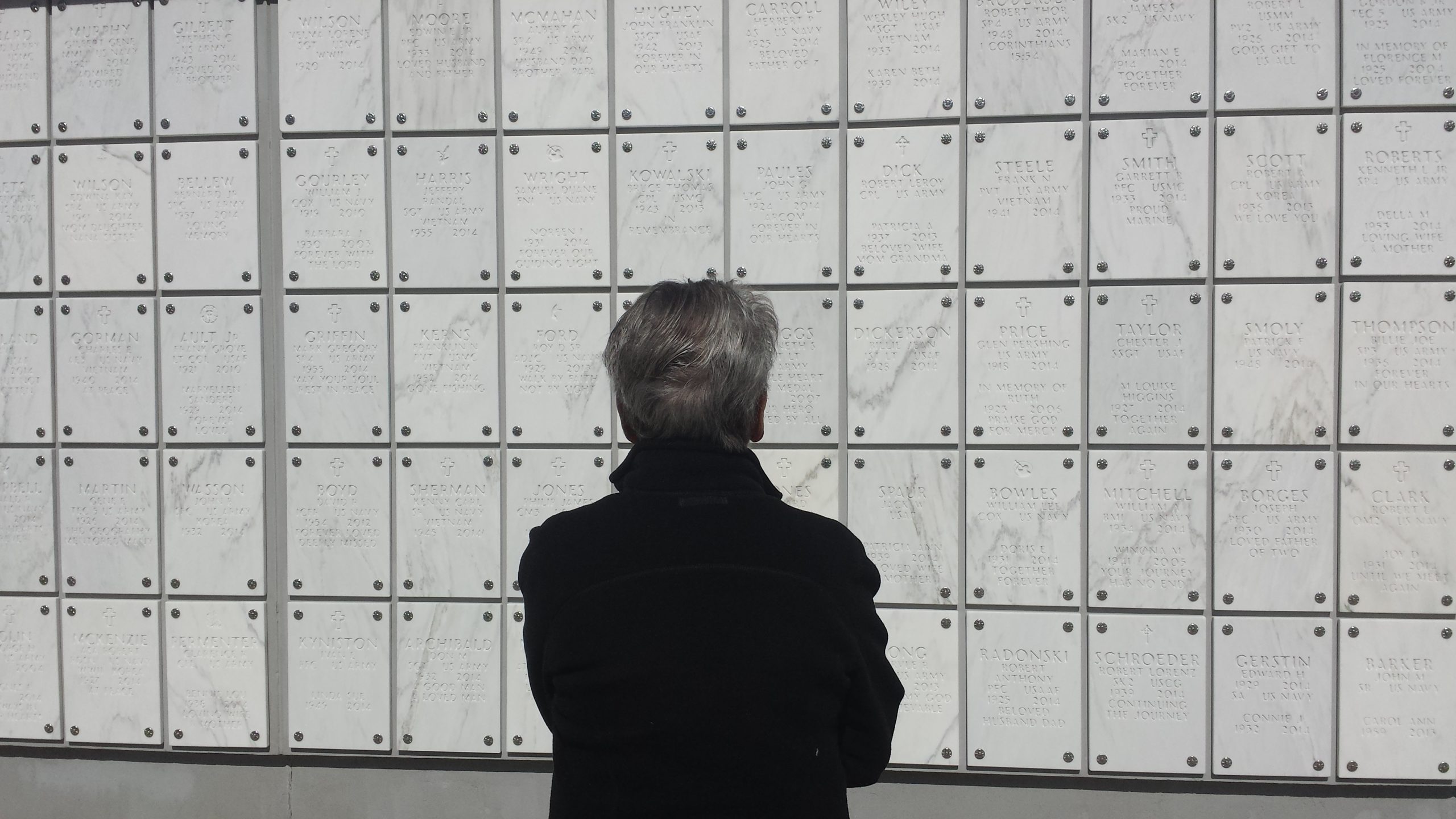

When my mother-in-law passed away, a neighbor sent my father-in-law a sympathy card with the message, “Remember, life is for the living.” Initially, it felt dismissive of grief, but over time, I saw its wisdom. Letting go isn’t about forgetting—it’s about honoring memories while creating space to heal and continue your own journey.

Decluttering after a loved one’s passing is deeply emotional. Whether you’re facing an urgent need to clear out a home or taking your time, this guide offers practical and compassionate advice to navigate the process.

Understanding When You’re Ready

There’s no set timeline for decluttering after a loss. Grief is personal, and your readiness depends on your emotions, not just time passed.

Assess Your Readiness – do the items bring comfort or cause stress?

- If they bring peace, keep them longer.

- If they feel like a burden, it’s okay to let go.

- Move at your own pace— it’s your call.

When You Must Declutter Quickly

Sometimes, external factors like selling a home, or legal deadlines force a faster process. Acknowledge your emotions while focusing on practical decisions.

Tips for when you have limited time to declutter after a loved one passes:

- Set clear priorities on what to keep.

- Get help from family, friends, or a professional organizer.

- Use a sorting system with labeled bins/boxes.

- When offering items to others, set a deadline: “I’d love to pass this along if you’d like it. Please let me know by [date].”

- Accept that quick decisions are sometimes necessary.

The “Spark Joy” Approach

There’s hardly a more fitting moment to apply Marie Kondo’s advice—keep only what sparks joy—than when deciding what to do with a loved one’s possessions. Without that one clear, uplifting standard, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by guilt, uncertainty, or the weight of obligation.

Turning your home into a replica of the Raiders of the Lost Ark warehouse isn’t going to serve anyone. Keep what genuinely lifts your heart or enriches your life. Let the rest go.

If it sparks joy, keep it. If not, release it. That’s your true north.

Declutter at Your Own Pace

Grief and decluttering have no deadlines. Some people prefer a gradual approach, while others need closure through a quicker process. Choose what feels right for you.

Signs It’s Time to Start Decluttering

If you’re unsure when to begin, consider these indicators:

- Storage Struggles: Renting storage can delay decisions and add costs. Avoid the long-term storage trap.

- Clutter Disrupting Your Life: If inherited items overwhelm your space or interfere with your home’s functionality, it’s time to take action.

- Available Support: If family, friends, or professionals offer assistance, take advantage of their support when it is available.

Start with the Least Sentimental Items

Sorting through a loved one’s possessions can feel overwhelming. Ease into the process by:

- Beginning with food, toiletries, or household goods.

- Tackling large items first (e.g., furniture, bed, car) for quick progress.

- Gaining confidence before addressing highly sentimental objects.

Seek Support

Decluttering after a loss is emotionally and physically taxing. Don’t hesitate to ask for help:

- Family & Friends: Open communication can ease tensions and prevent conflicts.

- Remote Assistance: Loved ones who can’t be there physically can still help in a variety of ways, e.g. researching donation/recycling options, medication disposal or coordinating logistics.

- Professional Organizers: Hiring an expert provides guidance and efficiency.

Preserve Memories Digitally

Photographs or video can be a powerful way to keep memories alive without holding onto every physical item.

Benefits of Taking Photos or video before you start:

- Upload images to a shared folder so family members can view and choose items remotely.

- Digital memories take up no physical space but preserve sentimental value.

Finding Meaningful Destinations for Items

Finding a “good home” for things can make letting go easier. Consider:

- Donations: Give clothing, books, or furniture to charities your loved one supported.

- Family Heirlooms: Offer special items to extended family members.

- Returning Meaningful Gifts: If you know who originally gifted an item to the deceased, offer it back as a keepsake.

- Institutional Donations: Museums or libraries may appreciate unique pieces.

Managing Unintentional Losses – (aka when things go wrong).

In emotional or rushed decluttering, some things may get misplaced, donated or broken by mistake. If this happens, practice self-compassion.

Preventative Tips:

- Set aside a designated space for sentimental items.

- Use labeled bins for “keep,” “donate,” and “discard.”

- Remind yourself that memories exist beyond physical objects.

Letting Go and Embracing Joy

One of the hardest parts of decluttering after loss is allowing yourself to feel joy again. Some worry that moving forward means forgetting, but joy does not erase love. Letting go of inherited items isn’t about forgetting your loved one—it’s about making space for the present. The items you choose to keep should be reminders of love, not obligations of grief.

By decluttering with care and intention, you honor both your loved one’s memory and your own well-being. With time, the process can bring peace, clarity, and the freedom to embrace life fully once more.

Support for Navigating Grief, Loss and Change

Sorting through inherited belongings can stir up complex emotions. If you’re looking for support during a time of grief, loss or change, Palmyra Bakker, an English-speaking grief counselor in Amsterdam, offers a compassionate space to help you navigate the emotional side of this process.

I’m Sheila, your opruimcoach/professional organizer. Each month I’ll drop fresh organizing inspiration, smart tips, and a nudge to let go of what doesn’t serve you. Sign up now and get organizing inspiration without adding to your clutter pile!